How does trauma link to speech and language disorders? Sarah Hine and a team of graduate researchers used their own experiences with vulnerable populations to guide speech pathology protocols.

Prior to pursuing her graduate degree in speech pathology at the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences, Sarah Hine, who graduated in May, worked with survivors of sex trafficking in India. Well before the COVID crisis curtailed international travel, Hine spent three years coordinating nonprofit efforts in the United States and India to help young girls who had escaped from brothels in Mumbai and Calcutta. She provided support to India-based organizations that guided the girls—mostly teens, some as young as 10—through the difficult process of psychological and physical healing.

As she befriended the young women, she observed that many struggled with communication. Some were essentially nonverbal, reluctant to engage with others and preferring to sit in a corner with their ear phones on. Others showed signs of cognitive deficits—seemingly slow to process conversation and refusing to make eye contact. None of those signs were by themselves surprising; reactions to chronic trauma manifest themselves in any number of ways. But Hine noticed a possible correlation between the extent of the abuse and the severity of their speech issues. “I started to realize that maybe there are some gradients depending on the type of trauma someone received or the length of exposure to a traumatic situation that might indicate impacts on language,” she said. But the available research on such links was small, and the guidelines for speech language pathologists even smaller.

As a graduate student, Hine helped to fill that gap. She drew from her personal experiences for a project in Associate Professor Adrienne Hancock’s research lab in the Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences. Hine was one of a group of students who investigated the intersection between language and complex psychosocial trauma. They looked at how trauma in vulnerable people—from survivors of sex trafficking to children in the foster care system—can manifest itself in speech and language disorders. Their research involved conducting literature reviews of past studies, examining clinical best practices and learning from other disciplines, such as social work, psychology and neuroscience. The goal, Hancock said, was “to inform ourselves and our clinical practices” and develop a resource guide for speech-language pathologists.

“We want to first educate ourselves on the effects of trauma across populations and then apply these learnings, providing a trauma-informed approach to all we serve.”

— Sarah Hine

Turning Experience Into Practice

Trauma-informed care, Hancock said, is playing an increasingly large role in education and healthcare—settings where most speech-language pathologists work. But guidelines for how to recognize the link between psychosocial trauma and speech disorders—along with recommendations for how to respond to them—are still in their infancy.

Hine and three other researchers—Caitlin McDonnell and Isabelle Nejedlik, both of whom also graduated in May, and second-year graduate student Madison Dull—approached Hancock with questions about how to do their clinical work with clients who had experienced psychosocial trauma. Like Hine, each had worked with vulnerable populations, including children with histories of abuse and neglect, veterans, refugees and incarcerated people. “We were all drawn to this work for different reasons but with the same end goal in mind,” Hine said. “We want to first educate ourselves on the effects of trauma across populations and then apply these learnings, providing a trauma-informed approach to all we serve.”

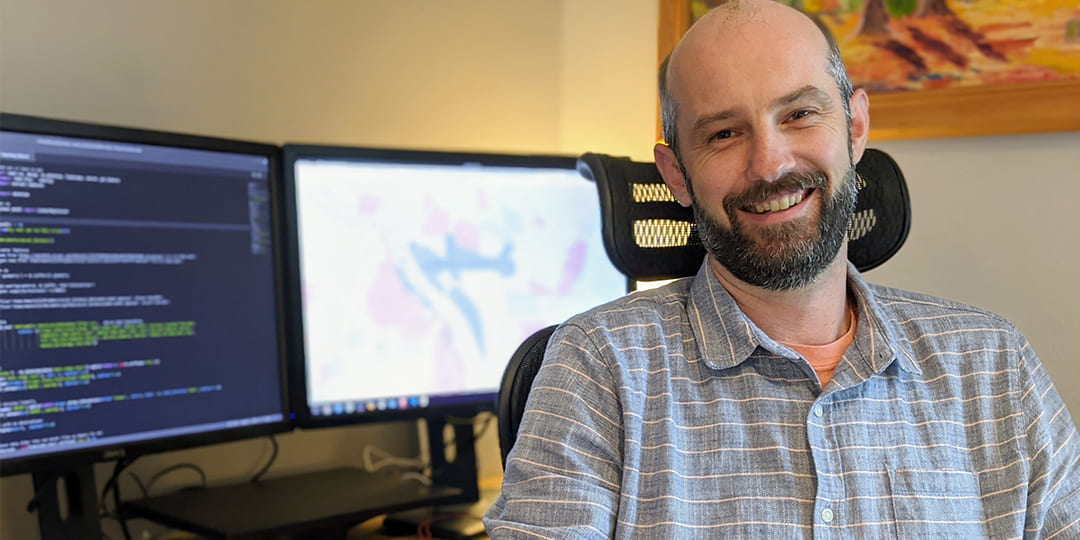

Main Photo: Inspired by her experiences working with survivors of sex-trafficking in India, Sarah Hine is helping devise a trauma-informed approach for speech-language pathologists.